Did you know the largest artifact at the South Carolina State Museum is its building? Read on to learn more about how the world's first electric powered textile mill became a museum.

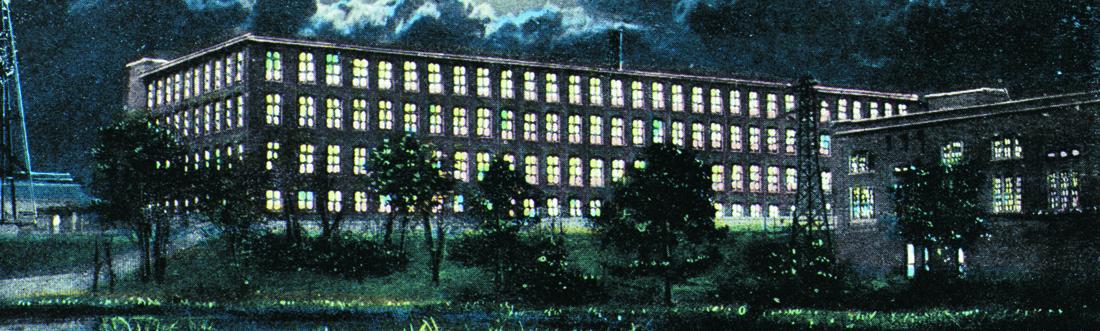

On April 15, 1894, Arethas Blood, president of Columbia Mills Company, pulled a switch to start the motors in the new Columbia Duck Mill. This event marked the first time that a textile mill anywhere in the world was operated completely by electric power. By the end of that year, the mill was in full operation, producing heavy cotton duck material.

The completion of the Columbia Canal, from the diversion dam above Broad River Road to Gervais Street, in 1891 ushered in an important era in South Carolina’s history. The Columbia Mills Company decided in 1893 to locate a new textile mill on the canal at Gervais Street because of the easy availability of water power. Construction began on April 18, 1893. Although there was a waterwheel at the canal, it became apparent as construction proceeded that it would be difficult to get the necessary power to operate the mill.

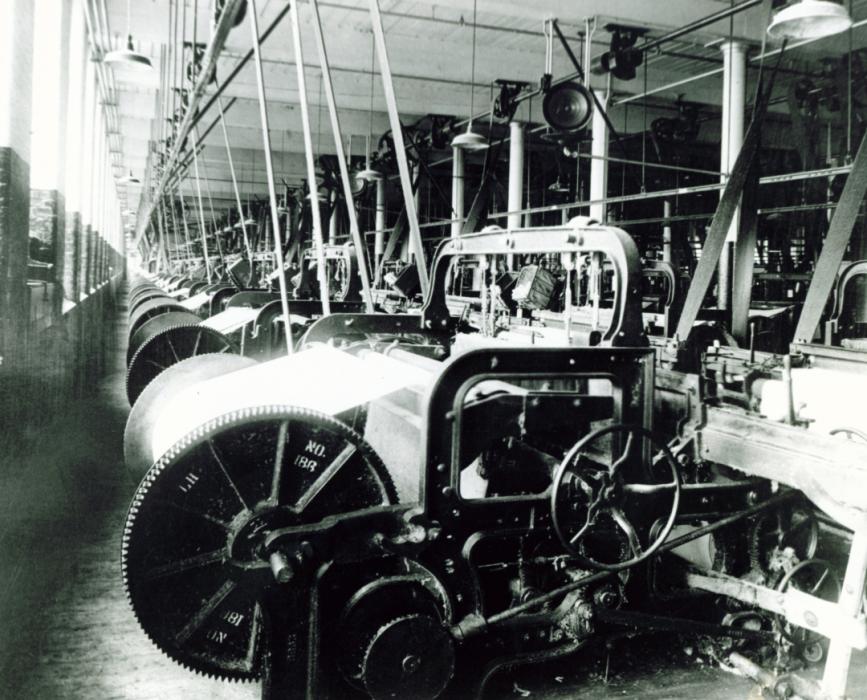

At this point the owners began to explore the possibility of alternate sources of power, including electricity. Sidney B. Paine of the General Electric Company suggested the construction of a hydroelectric plant on the canal and the installation of electric motors to power the textile machinery. Even though the largest induction motor ever built prior to this time was a 10 horsepower model, the General Electric Company took an order for seventeen 65 horsepower motors. Because the floor plan for the equipment in the mill was already completed and there was no space on the floor, it was decided to suspend the generators from the ceiling.

Columbia Mills interior showing loom machinery.

Most of the materials used in constructing the mill were of local origin. The three-foot thick walls of the original building, which runs east and west parallel to Gervais Street, were constructed with brick from the Guignard Brick Company, located on the opposite side of the river less than a mile downstream. The timber in the building, with the exception of the maple flooring, was purchased from W.B. Alderman of Alcolu, South Carolina, and the Fowles Lumber Company of Columbia. The granite sills for the windows and doors were quarried at A.R. Stewart’s quarry near Columbia.

In 1895-96, in order to provide space for additional machinery, a new wing was constructed, projecting north from the east end of the original building. When this wing was completed, the hydroelectric plant could no longer provide enough power, and the Columbia Water Power Company erected a new plant that is still in operation at the Gervais Street bridge. The original power plant, located about 200 yards up the canal from the new one, continued operating until 1927, when it was abandoned. The foundation of the old power plant is still visible on the canal bank.

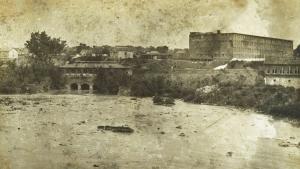

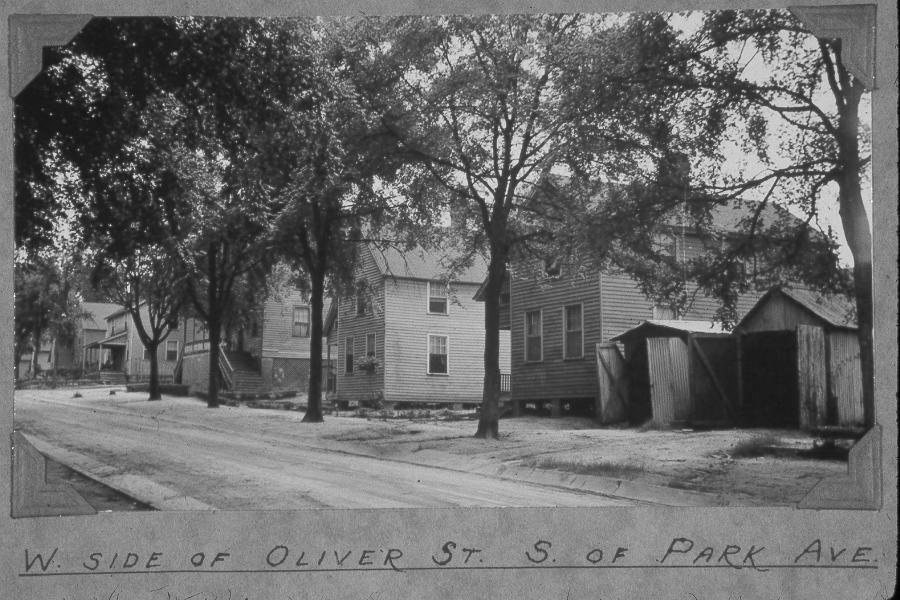

New Brookland neighborhood that sat across the river from the Columbia Mills and was where the mill employees lived.

At the time the mill was under construction, the company erected a mill village called New Brookland on the West Columbia side of the river. The mill continued to own the houses in the village until 1953, when it sold them to private citizens. Many of the houses have been restored by their owners.

The original General Electric motors served the mill for 33 years. When the mill switched to commercial electricity in 1927, these motors were retired, still in perfect operating condition. Several of the motors were placed in museums, including two at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, and one at the Charleston Museum. One of the original motors is now on exhibit at the State Museum.

Large group gathered outside the Columbia Mills Building, World War II era.

During World War II, the mill, by that time owned by Mt. Vernon Mills, Inc., played a major role in the war effort. In the year following Pearl Harbor it operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week, producing 1,500,000 yards of duck cloth per week that was used to make tents, tarpaulins, hatch covers, boat covers, gun covers, truck covers, collapsible pontoons, raft stretchers, cots, knapsacks, uniforms and shoes. In recognition of its records, the Mt. Vernon Mill was awarded on Oct. 27, 1943, the Army-Navy “E” flag, which is currently in the State Museum collections. In addition, the mill received the “T” flag from the Treasury Department indicating that more than 90 percent of its employees purchased war bonds.

In the fall of 1980, Mt. Vernon Mills, Inc. announced that it was closing the Columbia mill because of a declining market for duck product. Shortly thereafter, at the request of Gov. Richard W. Riley, the Museum Commission began to study the feasibility of using the mill for the State Museum. On Dec. 7, 1981 Mt. Vernon Mills, Inc. donated the building to the state.

Opening Day at the South Carolina State Museum in 1988. Image courtesy of The State Newspaper.

At present the usable portion of the mill consists of two wings. The original four story structure is 385 feet long and 192 feet wide. The four story 1895 addition measures 295 feet by 128 feet. The entire facility contains approximately 325,000 square feet.

The South Carolina State Museum opened in the building on Oct. 29, 1988. It is South Carolina’s - and quite probably the Southeast’s – largest and most comprehensive museum. Its four floors house four disciplines: art, history, natural history and science/technology and, in 2014, the museum expanded to include a 4d theater, planetarium, and observatory.